Regular visitors to the K-12 Cybersecurity Resource Center will note that the count of K-12 cyber incidents does not advance at a steady pace. While on average a public disclosure of a school incident occurs roughly every two to three days in the U.S., sometimes public disclosures of school incidents are less frequent (e.g., over the summer when school is out of session) and sometimes disclosures come all at once. One of the more significant ways that new incidents cluster is when a school vendor or partner (such as a non-profit, association, or other local or state government agency) experiences an incident that affects multiple schools across districts. Given that security incidents on the K-12 Cyber Incident Map are defined as something that happened in–or happens to–one or more schools in a single school district (or other public K-12 agency), school vendor/partner incidents can lead to the rapid addition of dozens of incidents to the Map.

Case in point: School vendor Total Registration, which according to must-read reports published on May 9, 2019 on DataBreaches.net (“Vendor used by schools to register students for AP and PSAT exams left personal information of thousands students unsecured“), recently experienced a significant breach of sensitive student data in its care. While only a fraction of the total number of affected school districts was disclosed in the original reporting of the incident, the number was still significant: 19 districts from 12 different states. The reporting by DataBreaches.net appears to have been independently confirmed when the Hartford Courant ran a story corroborating the basic facts of the story (“West Hartford officials warn parents of test registration platform data breach“), bringing the total count of publicly disclosed incidents attributable to Total Registration to 20 districts (so far). Of course, not all of the reporting in the Hartford Courant story seems to be accurate. For instance, DataBreaches.net unequivocally demonstrated that student data had indeed been accessed by security researchers, if not also unauthorized–and potentially malicious–third parties.

There are at least three important questions raised by the Total Registration breach:

How is the Total Registration breach being disclosed to affected schools, students, and their families?

While the Hartford Courant story suggests that district customers of Total Registration may be in the process of being contacted by the company, there is otherwise no evidence that any such disclosures are in the process of being made. As of today, no information about the incident is available on the website or social media accounts of Total Registration. No other public reports of the incident exist. Moreover, sometime after May 9, 2019 Total Registration removed the list of its current customers from its website. Thanks to Google, however, an archive of that page from April 7, 2019 remains available online.

DataBreaches.net advises parents of students who signed up for an AP test, the PSAT, or an IB examination in April to inquire whether their child’s school used TotalRegistration.net as their vendor for the sign-ups. That remains good advice.

In any event, the K-12 Cybersecurity Resource Center will continue to monitor public disclosures of school cyber incidents, including for mentions of data breaches related to this company.

Why is Total Registration collecting such sensitive data about students just to register them for a test? Are schools that use the service in compliance with federal and state student data privacy laws?

DataBreaches.net reported that Total Registration collected a range of student data, including:

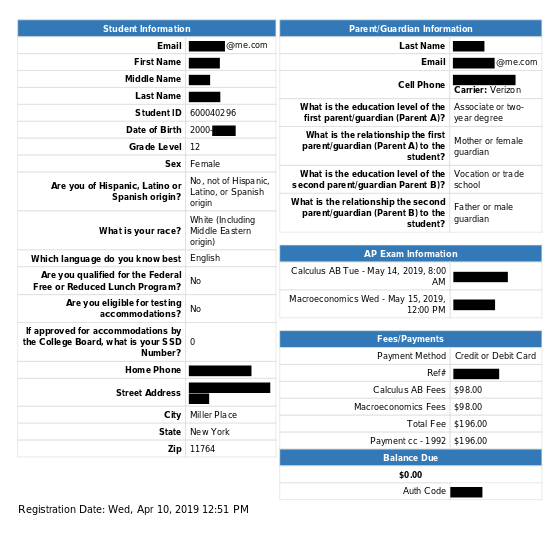

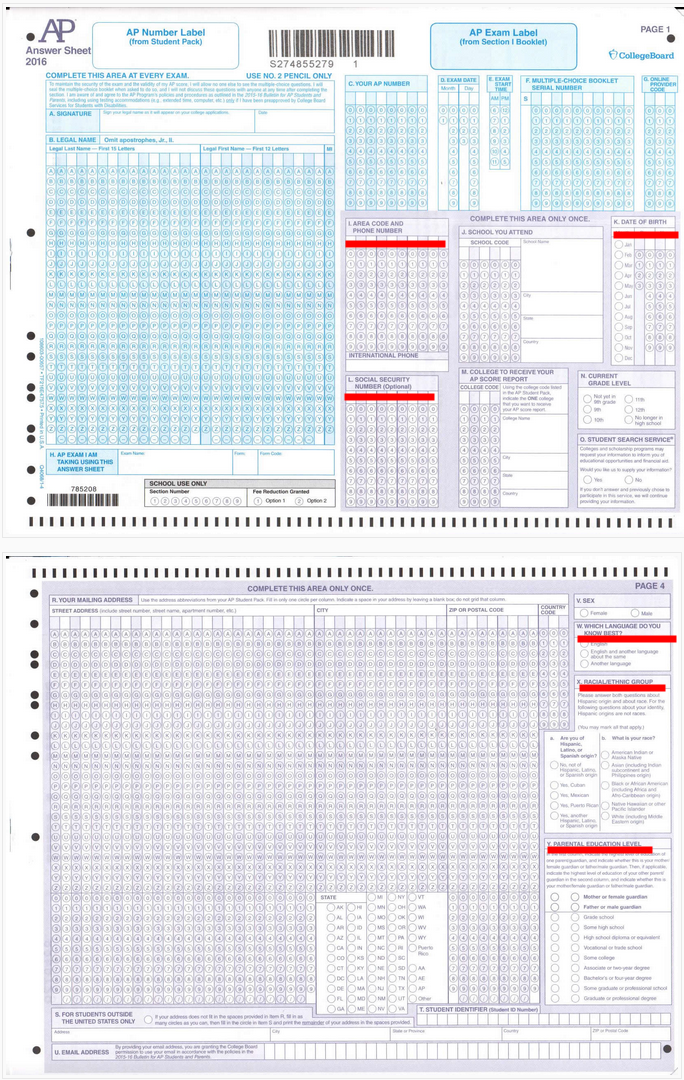

“students’ last and first names, their student ID number, their email address (which in many cases was a school-issued email address), their parent’s email address, their telephone number, their postal address, the AP exams they were registering to take, as well as when the exam would be and who was proctoring it….Some of the files contained students’ date of birth, as well as additional demographic information on students and their parents.”

A sample student registration confirmation offers more context:

On its face, this is the same sorts of demographic information that college admissions tests ask as part of their support for college/university-related marketing efforts. My suspicion was quickly confirmed by a support article posted on the company’s website (“Personal data collected“):

While I can’t speak to the value-add of the service that Total Registration offers as a third-party intermediary to college admissions testing services, I would be remiss if I didn’t note that the mere asking of these background questions raise their own student data privacy issues not only for the company, but also for the schools that avail themselves of their services.

The U.S. Department of Education outlined these issues–along with their recommendations for how districts could remain in compliance with federal student privacy laws–in their May 2018 guidance, “Technical Assistance on Student Privacy for State and Local Educational Agencies When Administering College Admissions Examinations [PDF].” That guidance summarizes the issue as follows:

“In connection with these college admissions examinations, testing companies administer voluntary pre-test surveys asking questions about a variety of topics ranging from academic interests, to participation in extra-curricular activities, to religious affiliation. We have heard from teachers and students, however, that the voluntary nature of these pre-test surveys is not well understood, and that each of the questions requires a response, and the student must affirmatively indicate in response to multiple questions that the student does not wish to provide the information. The survey’s multiple questions are designed to allow targeted recruitment, and students are specifically asked whether they would like to receive materials from different organizations, including colleges and scholarship organizations. For students who consent to being contacted by these organizations, the testing companies then sell this information to colleges, universities, scholarship services, and other organizations for college recruitment and scholarship solicitation.”

The re-selling of student data collected via the admissions testing process is big business and controversial (see, e.g., “For Sale: Survey Data on Millions of High School Students” published July 29, 2018 by Natasha Singer of the New York Times). In fact, the publication of this story in the New York Times led to the College Board’s status as a signatory in good standing of the Student Privacy Pledge to be placed ‘under review’ a mere two days later by the Future of Privacy Forum and the Software & Information Industry Association (“The College Board’s Student Privacy Pledge Status“). As of today, almost nine months later, the concerns about the College Board’s information usage practices with respect to these background questions remain unresolved. Given the relevance of that review to the specifics of this incident, the pace of the Student Privacy Pledge manager’s review is doubly disappointing.

For its part, Total Registration’s privacy policy does not acknowledge these issues. In fact, Total Registration does not post a link to its privacy policy as a footer on the pages of its site. Instead, its brief privacy policy can only be found via a search of its support site (“Privacy Policy“):

“Total Registration safeguards the privacy of both students and schools. All personal data is only used for the purpose of registering students for exams. This data is not and will not be sold, given or provided to any other parties. Coordinators at client schools are the only people who have access to their students’ registration data outside of Total Registration. Total Registration acknowledges that the student data is property or the school and the student. As such, the school and the student have the ability to manage the student’s data within Total Registration.”

That’s it, the entirety of the policy, apparently unchanged for the last four years (despite the release of new federal guidance on admissions testing and the passage of scores of state student data privacy laws since that time, including in Colorado where the company is based).

What does Total Registration’s incident response to date suggest about their data privacy and security practices?

The available evidence suggests the company:

- May have lax internal controls with respect to the security of its IT systems;

- Did not encrypt student data ‘at rest’ on at least one of its cloud servers;

- May or may not be notifying its school customers–or affected students and families–of the data breach incident;

- May have obscured its school customer list (previously published on its website) as a way to limit disclosure verification by schools, parents, the media, and other independent parties;

- May not be aware of (or potentially in compliance with) the evolving student data privacy regulatory landscape; and,

- Is not a signatory of the Student Privacy Pledge.

Since the final story about this incident won’t be written for weeks or months, there is still time for Total Registration to demonstrate its commitment to the duty of care required to serve the K-12 market. Here’s hoping they fully disclose to all affected parties and take the steps required of them to restore trust in their security and privacy practices. In so doing, I’d point them to the team at Schoolzilla, which in responding to a similar 2017 incident may have set the standard for responsible disclosure and response to a K-12 cyber incident by an edtech vendor.

A final thought: When schools outsource information services to third parties they are transferring cybersecurity and privacy risks to that company. However, this does not absolve schools of their responsibilities under state and federal privacy laws. This example points to the need for better data breach reporting requirements for student data breaches, as well as for easy-to-use tools to assist districts in vetting the security and privacy practices of all of their vendors. Some of these tools may be found in the ‘resources‘ section of The K-12 Cybersecurity Resource Center. Suggestions of other resources that may be of use to readers are always welcome.