UPDATE: Before reading this post, you may wish to read Hacking the ISTE18 Smart Badge for context,

Part of my interest in sharing my musings about the ISTE ‘smart badge’ was to crowdsource the R&D (such as it was) about the ‘smart badge’ surveillance system. As such, I want to begin this follow-up post to ‘Hacking the ISTE18 Smart Badge‘ with an expression of thanks to @BeaLeiderman and @joshburker for pitching in. In particular, @BeaLeiderman was the one who turned me on to what the beacon readers looked like and shared some interesting ideas about how they worked. For his part, @joshburker helped me confirm the functionality of the beacons and mobile app, what happens to them when the battery is removed and replaced (they appear to stop transmitting altogether), and – most interestingly – how one might not just read, but write data to the beacons. Also, thanks to @FrankCatalano, for pointing out that media were not offered smart badges. As near as I could figure from my conversations, vendors also were not offered smart badges unless they (also) registered as a conference participant. I did not see any ISTE or conference staff wearing smart badges.

This follow-up post is long and separated into several parts:

- Further insights into the ISTE ‘smart badge’

- About the ISTE ‘smart badge’ readers

- Thoughts on security/safety concerns

- Informed consent

- The problem of normalizing surveillance

Further Insights into the ISTE ‘Smart Badge’

After some difficulty using the original mobile app I recommended, I found a different free app made by the Chinese manufacturer of the badge (Minew Technologies). That app, BeaconSET, was far better at reading the smart badges as it automatically filtered out other Bluetooth-enabled devices that I was seeing, such as other phones, tablets, laptops, headphones, Apple pencils, and fitness trackers.

The user interface (UI) of the BeaconSET app was also much easier to interpret. As such, I could see that the badges were set to:

- transmit at maximum power: 4dBm (rated for 90 meter range, at the cost of battery life)

- broadcast only once every 900 milliseconds (the second longest interval possible, which should help conserve battery life)

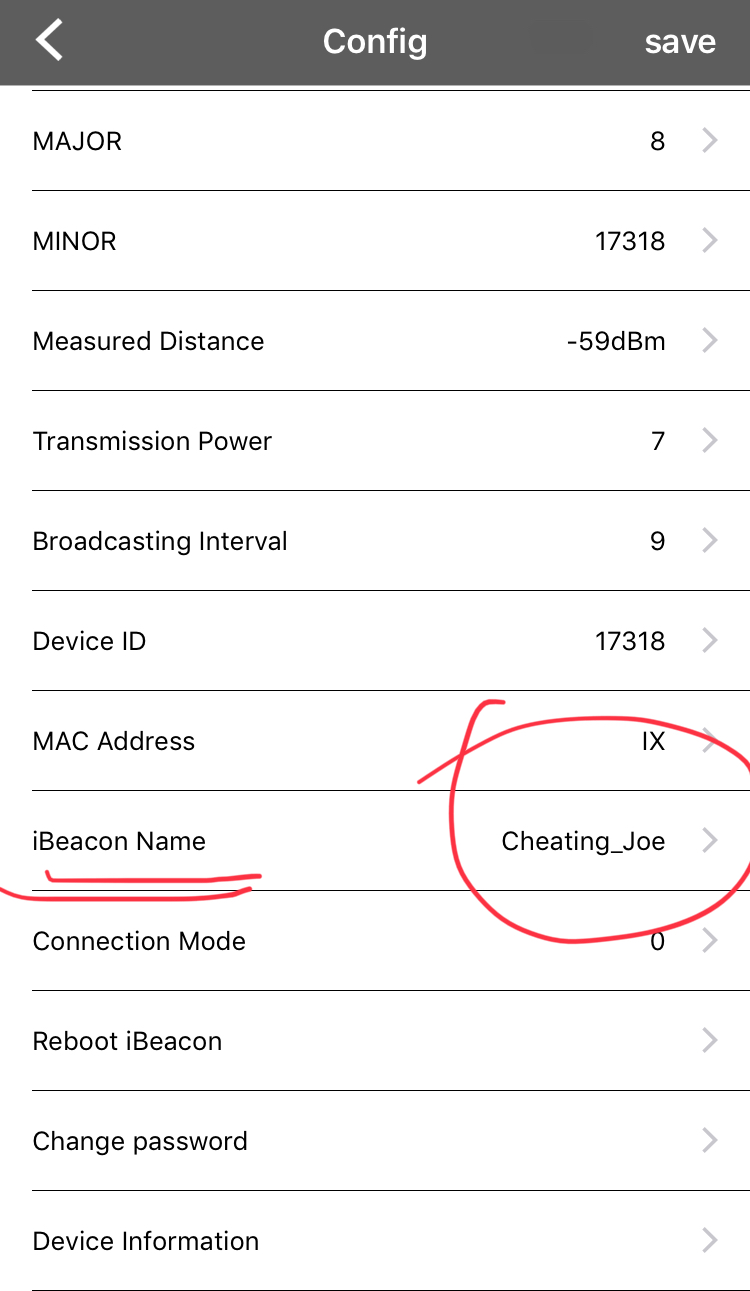

The UI also appeared to be designed to allow certain data values and settings to be edited, including the human readable name of the device.

Figure 1

An eight-value (letters or numbers only) password, however, was required to save any changes to the ‘smart badge’ itself. This is a good thing, as being able to modify the data that the beacon transmitted could make tracking of individuals even easier (changing ‘eventBit_12345’ to ‘sexy_Jane’ or ‘cheating_Joe’ or ‘terrorist,’ etc.). Having said that, so long as the beacon ID was unique and unchanging, nothing about writing to the beacon fundamentally changes the threats posed by wearing one. I have more to say on safety and security issues below.

About the Smart Badge Readers

I spent nearly all day Monday unable to locate a ‘smart badge’ reader. This is a testament to the fact that they were unobtrusive and also that readers were (apparently) not distributed on the exhibit hall floor (or, if they were, they looked different). Once @BeaLeiderman clued me in, I began to see them everywhere (and felt a little stupid for missing them). Many on Twitter seemed to have spotted them much more easily than I did initially. I can’t even hazard a guess as to how many were deployed (or redeployed) over the course of the event. There were a lot of them (always many to a room or common area).

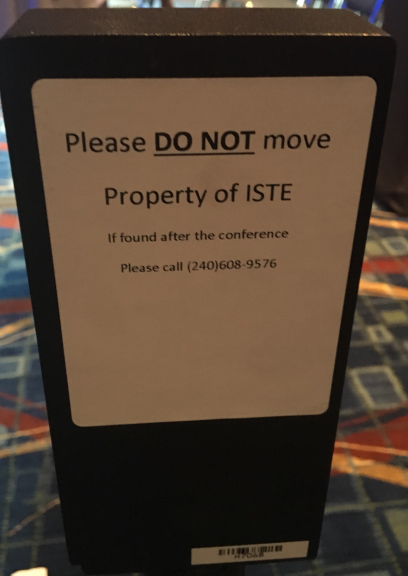

The reader itself is a black post with a small rectangular box on top (very similar to what you might see in the security line at airports, holding the flexible cord that designates how you must snake through the screening line). These posts were free-standing and not plugged into power or ethernet.

Figure 2

The rectangular box was marked with a big white sticker on one side, declaring that these devices were property of ISTE and that they were not to be moved.

Figure 3

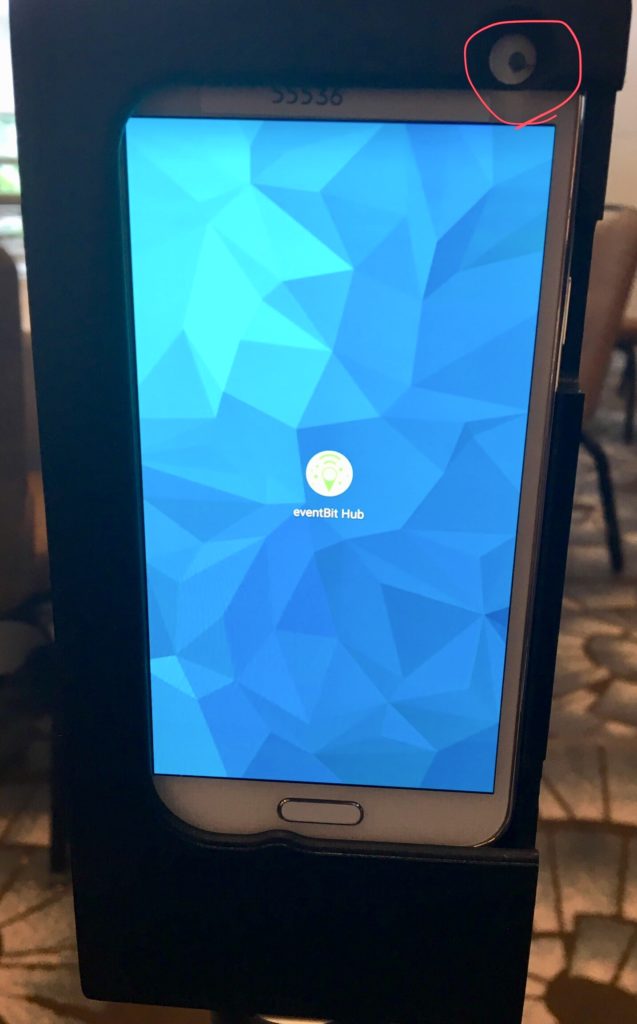

On the other side, was a sliding plastic door, that when opened revealed a stock Android phone (!!) running eventBit Hub software. The other notable feature of the rectangular case was that there was a hole cut in the upper right hand corner to allow for the phone camera lens to be unobstructed (circled in Figure 4 below). I have been hard pressed to understand under what circumstances the camera might be used (other than as – perhaps – an anti-theft measure). Others speculated it may be taking pictures of the room periodically as part of its tracking protocol, but I am not certain how valuable that would be as the orientation of the beacon readers seemed to vary randomly from room-to-room and reader-to-reader. Perhaps it is just a re-purposed case and it serves no function.

Figure 4

I was – and in some ways remain – intrigued by the notion that the ‘smart badge’ readers are nothing more than a stock mobile phone in a box. In some ways, this strikes me as an instantiation of a minimally viable product. Yet, as I talked it through with colleagues at the conference, there is a sort of logic. Battery-powered phones come with WiFi, cell service, and Bluetooth connectivity. This allows them to run all day without being charged (or maybe more, if optimized, and it looks like they were) and to periodically ‘phone home’ to EventBit to prepare and offer ‘real-time’ statistics to ISTE staff about traffic flow (and whatever else they may do with that data).

It also is hard not to be struck about what this ‘smart badge’ system says more generally about the use of cell phones as a surveillance tool.

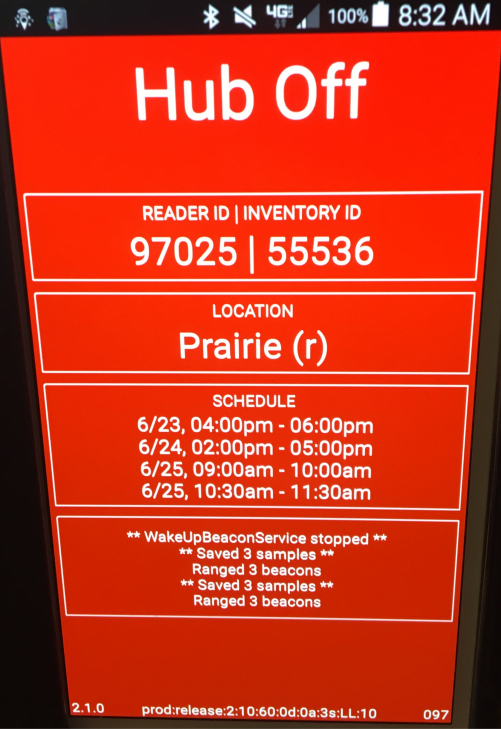

I did not appropriate a ‘smart badge’ reader to tear it down as it was clearly not my property (and I could not locate a freely available copy of the ‘EventBit Hub’ software), but in waking the screen on a number of readers I was able to glean a number of things.

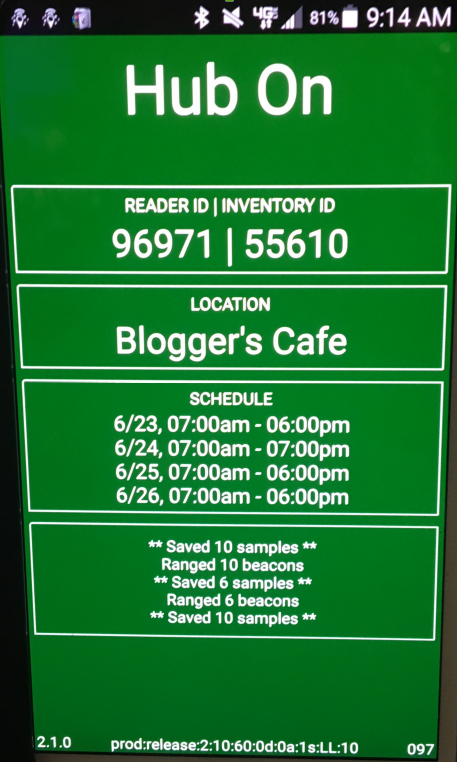

Figure 5

Figure 6

First, it appears that each ‘smart badge’ reader is meant to be in specific locations (as indicated by the ‘LOCATION’ field). This means that both ISTE and EventBit had to have met with a schematic of the conference center and make affirmative decisions about which areas of the conference were important to surveil and which were not. I also suspect that the price that ISTE paid for the system only covered a certain number of readers.

Second, the ‘smart badge’ readers also were each individually scheduled to automatically turn on and off over the course of the event. It appears that for presentation rooms the readers were only scheduled to turn on during scheduled talks. For common areas, the readers were functional during the conference’s primary hours each day.

Of note, there was no external indicator that indicated whether a ‘smart badge’ reader was on or off. The only way I was able to tell the state of the reader was to remove the panel and wake the screen.

Thoughts on Security/Safety Concerns

That Internet-of-Things (IoT) devices are insecure and can be used to harass and torment people (or worse) is not an imagined threat. The New York Times, in fact, ran a chilling story during the conference (“Thermostats, Locks and Lights: Digital Tools of Domestic Abuse“) highlighting examples of this occurring and its impact on the women so targeted. And, yes, in the vast majority of cases this is a story about men doing violence to women. Closer to home for #ISTE18 participants, Education Week recently reminded us that the K-12 sector is home to more than its fair share of #MeToo moments.

There are three points about the risks of what ISTE deployed at their conference to know: (1) the ‘smart badge’ is a really effective locator beacon, transmitting signals that are trivial to intercept and read, (2) you can’t turn it off, and (3) most people I spoke to had no idea how it worked. (I freaked out more than a few people by telling them what their badge number was by reading it from my phone. Most of those incidents ended up with ‘smart badges’ being removed and destroyed.)

Downloading a free mobile app, as I did, an attacker could easily track a specific badge and be notified when it goes out of or comes into range. With little technical skill, an attacker could use it to approach someone outside of the convention center (at a bar or restaurant or tourist attraction) and by employing social engineering techniques attempt to gain their trust. I myself was able to identify that there were over a dozen ISTE conference participants on my train platform on Wednesday morning bound for Chicago O’Hare. When one ISTE participant entered my train car at a later stop, that was trivial to identify. While there were no other ISTE participants on my flight back to the DC area, I located two badges in the baggage claim area (likely packed in someone’s luggage or carry-on).

A motivated attacker who knew in advance that this specific technology was being deployed, could purchase one or more long-range readers (e.g., Ubertooth One, the Ellisys Bluetooth Explorer, or the Frontline BPA® 600 Dual Mode Bluetooth® Protocol Analyzer, etc.), network them via WiFi/cell service, and write scripts to simplify the tracking of one or more unique badges. If the goal was to track a specific person, they would need to be physically proximate only once to determine the target’s badge ID. Once that was determined, they would not ever have to be closer than 270 feet (90m) including through walls – even further depending on the reader – to track your location accurately (+/- a few meters). They could write a script to notify them when, e.g., you came back to your hotel room or left – and which badge(s) were nearby. If someone had a late night visitor in their hotel room, but left before morning came, it would be trivial to record that information.

Informed Consent

I seem to recall having to accept some terms to pre-register for the conference online on the ISTE website. I have no recollection what it said and can’t seem to find a public record of what those terms were. Either I accepted them or I couldn’t pre-register. Just like the Terms of Service I have to accept to use software, I – like many others – just clicked the box to finish my task. As such, if there were terms relevant to ‘smart badges’ I missed it.

Now, having said that, I first learned that ISTE was deploying ‘smart badges’ in a June 8 email addressed to me (subject: “ISTE 2018 final confirmation”). This was a long email, but – sandwiched between the hours of the registration desk and the on-site payment policy (no cash) – the following notice was included:

Smart badges

This year, ISTE is excited to offer smart badges! Attendees who wear a smart badge will receive a customized “ISTE 2018 Journey” report shortly after the conference. The journey report will include a listing of all the sessions you attended and links to any digital resources the session offered. The badges will provide ISTE with information on session attendance and content selection to aid us in future planning. Visit our smart badge FAQ for more info.

Upon reading this information, I published a blog post about it (“Must-Have Technology Gear to Bring to ISTE 2018“), which itself detailed what I could glean about the technology and the privacy policy of the company behind it.

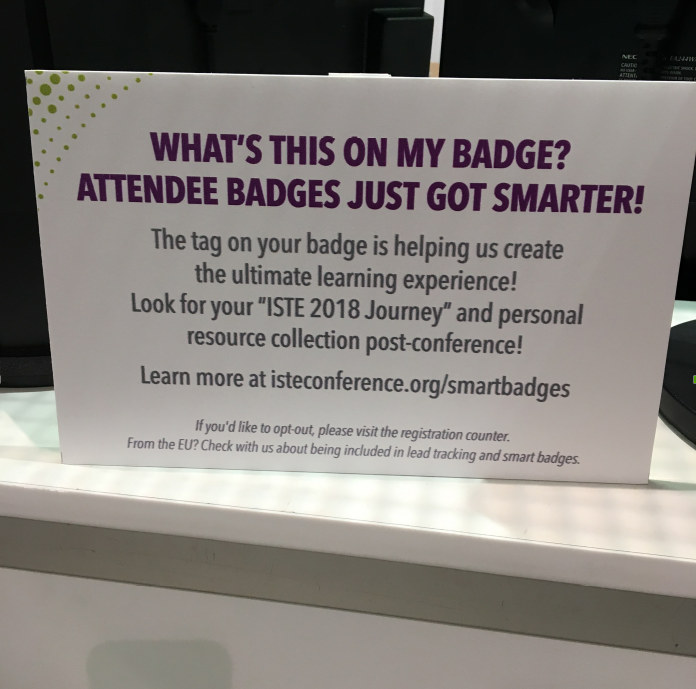

At the registration desk where I picked up my badge on Sunday, I also noticed these signs.

Figure 7

Yet, despite the email and the physical signs at the registration desk, many people asserted to me that they never received notice of the use of the ‘smart badge’. Of those that did, many had no idea how it worked. They thought it was just a QR code for vendors to scan. Many didn’t understand that it was a battery-powered transmitter without an off-switch. Not a one was happy upon learning what I discovered.

Did ISTE offer enough information to participants so they could make an informed judgment about the value of wearing the badge vs. the potential risks? Should wearing the badges have been an opt-in vs. opt-out decision for participants? For educators trying to manage the privacy and security risks of edtech in their own classrooms, what lesson does this incident impart about best practices and informed consent?

As ISTE and its members collectively mull through these questions, I look forward to hearing about the reactions to the after-conference reports that participants are slated to receive about their movements and presumed interests. Will folks feel like it added value? I bet for some segment of participants receiving that email will trigger concerns they didn’t even know enough to worry about in the first place. It will be the first time they realized their movements have been tracked.

The Problem of Normalizing Surveillance

Throughout this post, I’ve made sure to keep my references to the ISTE ‘smart badge’ in quotes. It is not smart. It is a Bluetooth location tracker – commonly used to locate lost cats, keys, and luggage – branded with words that connote innovation and trendiness and hence make it socially acceptable to track people. See how it is marketed for other, more common use cases:

- The best Bluetooth trackers for keeping tabs on your stuff

- 10 Bluetooth-Tracking Devices To Keep Your Belongings Safe

- How to Keep Track of Your Stuff with Bluetooth Trackers

- Best Bluetooth Trackers

Same tech, different branding, designed to obfuscate its purpose and avoid straightforward conversations about privacy and security trade-offs. This is big business (“Your Customers Are Moving Beacons, Are You Listening?“), according to the Location Search Association.

When people location trackers are marketed as ‘smart badges’ by trusted brands (like ISTE), when their operations are not explained, and when the technology is obfuscated, people become de-sensitized to practices they may otherwise object to.

Did the people in these pictures know they were socializing and learning in an environment where each of their movements were tracked within a meter of accuracy? Did they understand how these data will be used, how it is secured, and with whom it will be shared? Do they each think the cost-benefit of sharing these location data are worth the yet-to-be-sent conference summary emails? Did the surveillance system actually allow ISTE to make adjustments in real-time to popular sessions that were turning away participants?

Figure 8

Figure 9

Figure 10

Figure 11

Many – but not all – at ISTE may feel like they have nothing to hide or the risks are trivial. I am of the personal opinion that this is privileged, short-sighted, and dangerous.

Some celebrated George Orwell’s birthday during ISTE. What stories might he have told of the world we are creating for our children? Of ‘smart badges’ and ‘smart classrooms’? Of ‘personalized learning’?