The unprecedented large-scale closure of school buildings due to the coronavirus pandemic has resulted in a rush to online learning solutions. With little to no advance warning or planning, school districts – and their IT teams, such as they may be – have had to make the best of a bad situation and quickly. As I have asserted:

Most school districts are desperate to get any online system up and running, ignoring…standard protocols for vetting services, said Douglas Levin, president of EdTech Strategies, a consulting company. “Those have been thrown out the window for expediency’s sake.”

Criteria for decision making is driven primarily by cost and ease of use. Any training on how to use new tools and systems would have to come later, to say nothing of the more intensive work required to help educators re-think what it means to not be teaching in-person but online. As such, it is fair to say that school districts – and individual educators – have been driven to use tools and services without anything approaching the normal preparation and due diligence most school districts undergo.

On March 13, 2020 enter Zoom: “Exclusive: Zoom CEO Eric Yuan Is Giving K-12 Schools His Videoconferencing Tools For Free.” For many, Zoom appeared to be the right tool at the right time for the right price. And, indeed, usage of the service hit all time highs along with its stock price only a few short days later.

This makes the story of the last month remarkable. While much ink has been spilled by reporters in covering some of the company’s questionable marketing claims (“tomayto, tomahto“), security weaknesses, and privacy practices, the issue that has captured the attention and action of education policymakers, leaders, and teachers seems almost trivial by comparison: the ‘trolling‘ of online classes and school meetings AKA ‘Zoom-bombing’ or ‘Zoom raiding.’

Adapted from Electronic Frontier Foundation CC BY 2.0 https://flic.kr/p/fxDBpK.

As of today, the K-12 Cyber Incident Map has documented 19 Zoom-bombing incidents affecting K-12 public school districts – from elementary school classes to school board meetings. Anecdotal reports suggest the practice is much more widespread than I have been able to document (e.g., a simple search of YouTube finds numerous videos and compilations posted by trolls of their Zoom-bombing exploits). Such anecdotes also provide insight into the personal impact of these incidents:

Initially blamed on unforeseen user behavior by Zoom CEO Eric Yuan – who surely could have foreseen this possibility if he had only spoken to those who work in schools day-in and day-out – these incidents underscore the dynamic, cat-and-mouse nature of online attacks, as well as the idiosyncrasies of the IT security and privacy challenges facing K-12 school districts.

Initial public reports – as early as March 17, less than a week after Zoom made its free offer to schools – suggested incidents were only occurring for those online meetings and classes where Zoom meeting IDs were publicly posted on the internet and not password protected. Online trolls could and did find such meetings via simple online searches. (Indeed shortly thereafter, public reports emerged of hackers who had demonstrated how trivial it was to build automated tools to scan the internet and find massive numbers of unprotected Zoom meetings.)

On March 20, the same day that the New York Times profiled the growing issue (“‘Zoombombing’: When Video Conferences Go Wrong“), Zoom responded by taking its first step to protect its platform and users: a blog post on security best practices for hosting Zoom meetings and classes.

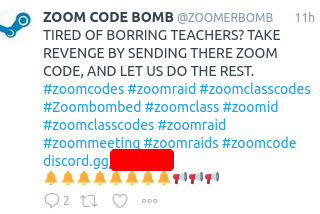

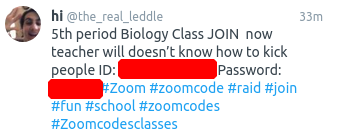

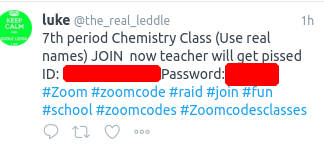

What was unanticipated by some of the expert advice and commentary framing the issue was the apparent fact that students themselves were sharing Zoom class IDs **and passwords** on social media and forums in an attempt to invite the disruption. A practice that continues to this day:

Each of these screen shots from Twitter were taken on April 13. Coupled with scammers phishing Zoom credentials from unsuspecting users and the re-selling of hundreds of thousands of Zoom credentials on hacker forums and the dark web, it is abundantly clear that a combination of meeting IDs and passwords alone is wholly insufficient to secure Zoom classes and meetings from unauthorized access.

Weeks after its free offer to schools, Zoom would institute changes so that education users – by default – would be better protected from Zoom-bombing (though still requiring action by school district IT staff to implement fully). No doubt this move was made because of intensive media scrutiny, alerts by federal law enforcement about the safety of Zoom and related products (“FBI Warns of Teleconferencing and Online Classroom Hijacking During COVID-19 Pandemic“), and major defections from the platform, including by school districts such as New York City. Zoom CEO Eric Yuan himself admitted that the company didn’t have experience working with schools and all that may entail:

There remains conflicting expert advice on whether it is the right thing for schools to abandon the platform in lieu of other alternatives. For example: “A Partial Defense of Zoom” (April 4), “Experts question abrupt decision by New York City to ban Zoom from use in all public schools,” (April 7), “This Zoom Hate is Silly” (April 10), and “Zooming” (April 13).

Nonetheless, much of this and related online commentary about schools’ use of Zoom and whether it remains a viable service for educators remains divorced from the actual threats and IT challenges facing school districts.

Enter Nathan McNulty of OpsecEdu who penned a must-read analysis entitled, “How Zoom failed to understand K-12 education.” As he writes: “The problem is there are a lot of weird things about K-12 education that few know about unless they work in the space.” (Related: For school district IT staff, Nathan also documented his experiences in working around the Zoom administrative console to accomplish some common education-specific tasks.)

On Twitter, another school district IT leader – Rachel Wente-Chaney – shared her thoughts about Nathan’s Zoom analysis along with her own gems of wisdom:

As expected, @NathanMcNulty crafted a thoughtful review. We have a day of reckoning ahead of us. I’m threading wonderings/thoughts again this Saturday morning so I don’t forget them when we transition to post-pandemic life. (Rambly thread ahead, in screenplay format. ?) https://t.co/MwtBY1hBrT

— Rachel Wente-Chaney (@rwentechaney) April 11, 2020

These are unprecedented times, and I think it therefore important to occasionally pause and reflect on the lessons we should draw from incidents such as this one. For me, three lessons in particular are top of mind.

First, much of the conventional wisdom around K-12 IT has suggested that school districts would do well to outsource as much of their IT operations and services to third-parties better equipped to manage complex IT equipment and online apps as they can. Indeed, no one has seriously suggested that school districts develop and deploy alternate education-specific videoconferencing technology on their own servers in responses to Zoom’s actions. Nonetheless, this incident underscores how important it is for school districts to vet and hold accountable the third-parties with whom they work. Realistically, this task is not one that school district leaders and policymakers should assume that can be accomplished well by most school districts. I’d further note that one of the trends that emerged in the report, “The State of K-12 Cybersecurity: 2019 Year in Review” was that of third-party risk:

“Since the K-12 Cyber Incident Map launched, it has documented numerous vendor- (and other third-party-) related security incidents involving unauthorized access to student and/or educator data. These include incidents involving: ACT, Blackboard, Chegg, Choicelunch, Edmodo, Elsevier, Follett, GameSalad, Graduation Alliance, K-12.com, Khan Academy, Florida Virtual School, Leadership for Educational Equity, Maia Learning, Naviance, Pearson, Pennsylvania Department of Education, Questar, Schoolzilla, the Texas Association of School Boards, and Total Registration. While the number of public disclosures rose to new highs in 2019, many questions remain unanswered regarding the state of K-12 vendor- and partner- security practices.“

Perhaps 2020 will bring with it a more serious consideration about the standards the public education system (and the taxpayers that support it) should hold its vendors and partners to with respect to privacy and security.

Second, the issue of Zoom-bombing – much like prior incidents experienced by Kahoot!, which has itself been plagued with bots – underscores that the threats facing school district IT systems and apps are not merely from malicious ‘outsiders,’ but also from school community insiders, including students themselves. It is for that reason that school districts and their vendors would do well to focus their IT security efforts as much on the actions of individuals already a part of their community – and authorized to be using approved classroom apps – as on outsiders (a concept known as ‘zero trust‘). In some cases, this may require a radical re-engineering of popular edtech apps and services; nonetheless, such efforts will could go a long way to improving the privacy and security risk management posture of school districts.

Third and finally, the speed with which Zoom has issued fixes and updated client software in the midst of scrutiny is impressive. It is vitally important that those school districts that continue to use Zoom ensure that teacher and student Zoom clients are kept up-to-date. While deploying software patches in a timely manner is a cybersecurity best practice, the reality is that it can be complicated to do at scale – especially for school districts that may rely on legacy apps and services and older models of computers and operating systems. In a time of remote learning, the challenge is of course magnified.

The story of Zoom – and its use by schools during the pandemic – is still being written. Here is hoping that the subsequent chapters have a happier ending.